In her new book “Listening in the Dark: Women Reclaiming the Power of Intuition,” award-winning author, activist, and actress Amber Tamblyn set out to examine our relationship with gut feelings and intuition in the modern age. It’s a gift she believes most people have been taught to ignore in favor of making decisions based on logic and evidence. “I believe our intuition — the connection between what our bodies can tell us and our minds can compel us — is the most vital tool we have to fight with in a world that continues to wage war against the feminine,” she wrote on Instagram.

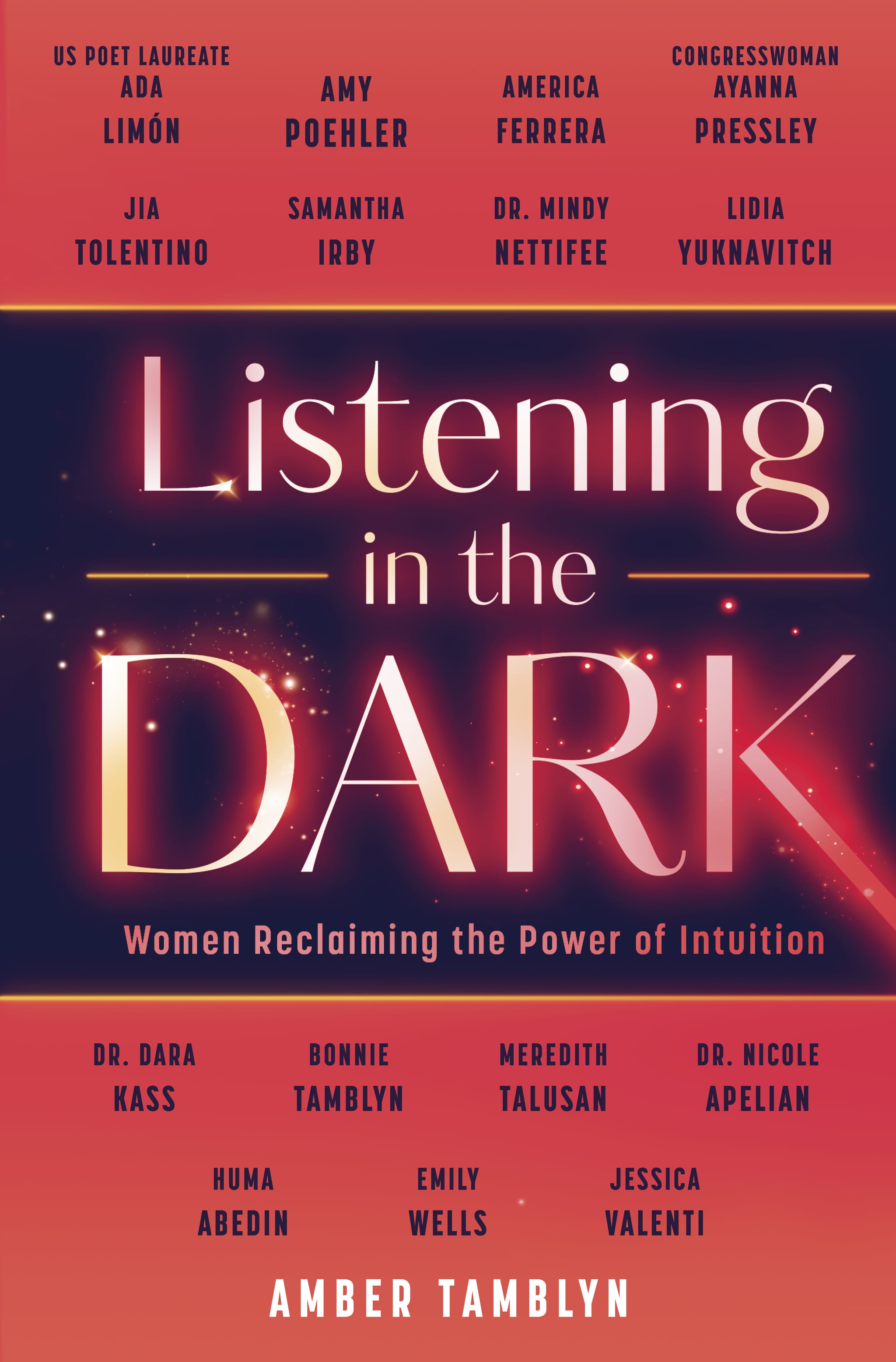

Published with HarperCollins, this collection of conversations and essays edited by Tamblyn includes reflections from Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley, comedian and actor Amy Poehler, poet Ada Limón, and writers Jessica Valenti, Lidia Yuknavitch, Jia Tolentino, Samantha Irby, Huma Abedin, and Meredith Talusan, among many others.

In this excerpt from “Listening in the Dark,” Tamblyn sits down with her “The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants” costar America Ferrera, who talks about disassociating from her body and intuition while growing up in an era of exceptionally narrow beauty standards — and later, how she worked through emotional and physical trauma to reconnect with her body.

Amber Tamblyn: Let’s talk about what it takes to get to this place in our lives where we better understand our intuition. I’m not sure I’m completely there — in the knowing — and I’m almost forty years old. I don’t mind it, that I’m still open to the possibility that my relationship to my intuition and what feels right or wrong is still being defined. I’ve definitely come a very long way since my childhood, as have you. From the fifteen years we’ve known each other —

America Ferrera: Girl, it’s been almost twenty —

AT: Almost twenty years! From the almost twenty years we’ve known each other, we’ve seen each other go through so much. So. Much. Death, marriage, failure, success, children, revolutionary political movements, crises both existential and literal. We’ve seen each other through all of it. And we’ve both worked really hard to get here, pushing past things that have terrified us, hurt us, held us back, challenged us. To get to this place where we can really hear what our intuition is telling us, about our physical health, mental health, emotional health, and psychological health.

AF: Very true.

AT: We both carried a lot of anxiety as kids — pretty bad anxiety — and a sense of feeling nervous about outcomes. While we had very different upbringings, we were still both child actresses in an era where girls and women were treated differently than they are today, and of course yours was compounded even further by being a woman of color. You’ve come such a long way from that girl you once were. Do you remember if you had any connection to your gut when you were younger, in the way that you do now? Maybe you were that in tune with yourself then, but you couldn’t articulate it at the time? Or do you think it’s a thing you found later on in your life?

AF: I’ve always been a very sensitive and tapped-in person, especially as a child. From as young as I can remember, I was always feeling whatever unspoken dynamics were happening in the room. I’ve always had a heightened radar for that. I think most children do. But I didn’t know to trust my own feelings, and I certainly didn’t know what to do with those feelings once they were acknowledged in my body, when and if they were trusted. For instance, several years ago, when I was learning about my intuition and how to harness it, I spent a whole year training for my very first triathlon. It was a really, really, really big deal for me —

AT: Right, I remember this —

AF: Because of all of the stories that I have about my body. I had this whole story about this car accident I was in when I was a teenager, and how I hurt my shoulder, and that hurt extended out to other parts of my body, and in a way, became a crutch for me — a reason not to deal with the other traumas of my body. It was true, I was in an accident, and the pain was real, but the story about the origin of the pain was not.

How can you trust something— a body that houses your intuition — when you’ve been told your entire life it is wrong?

AT: What do you mean?

AF: Yes, I had injured myself in a car accident, but no, it was not and could not be the source of all the pain I was feeling. Because when I really thought about it, when I began to ask questions of myself, the pain actually began way before that car accident; it began somewhere in my childhood. The car accident just brought attention to it. And by the time I was twenty-five years old, I was in crippling pain all over. I told myself my neck pain and back pain were chronic and would always be there. That I’d never be able to do anything athletic, I’m just not built that way, that this kind of suffering is just normal. The story I’ve told myself about that pain is how I’ve been able to feel disconnected from my body’s power, from its usefulness as a tool beyond something I just happened to inhabit. I had to actively transform my relationship to my body to change the story of what my body could mean to me.

AT: That is so powerful. So, you understood that to connect on a deeper level with your gut, with your intuition, you first had to not just heal your body but heal the story your body had been telling you your entire life, that it couldn’t be trusted because it was forever injured.

AF: Exactly. My relationship to my body also changed my emotional life. I realized it was all one and the same. There was no cause and effect. It was like you had to deal with both at the same time because that’s where emotion lives. I realized that everything I’ve ever experienced, every emotion I’ve ever had, every trauma, every joy, every memory has happened in this one vessel. This, right here, is where it all lies. Training for that triathlon was so confronting because it made me think about all the dissociating I have done — I have had to do to protect myself — since I was young. Because the truth is, it always felt uncomfortable to be in my body.

AT: How so?

AF: There were so many ridiculous expectations placed on women’s and girl’s bodies back then, when we were growing up, and under the public eye, no less. It was the era of Britney Spears, of tween movies starring rail-thin actresses, none of whom were of color. This is why the first film I made at seventeen years old, “Real Women Have Curves,” was so revolutionary — because those kinds of bodies and stories just did not exist on-screen. But the existence of that film felt like an anomaly, not a normality. There were so many ridiculous standards about what was the right way to look or the right way to be, and I was constantly being told I was none of those things, and so that’s the story my body latched on to. Living in my body — feeling in my body without anxiety — was not something I did or knew how to do. I had been taught from such a young age that so much about my body was not right, from the way that I looked to the way that I felt. But how can you trust something — a body that houses your intuition — when you’ve been told your entire life it is wrong?

AT: So you literally had to start from scratch with your body. You had to start over and teach it a new story.

AF: Yes. I distinctly remember the moment: I was actually at your house upstate, on your big trampoline. I jumped two times on the trampoline and started crying because my neck and back hurt so badly. I was twenty-five years old! I was otherwise in good health and had no reason to feel like this. I knew right then and there I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life feeling this way. And that’s when I really started to deal with the physical pain and how much it was linked to so much emotional pain, for so many years and for so many reasons. And they fed into each other. How could they not? This was the story! My story. My emotional pain causes trauma, and then —

AT: The trauma causes the emotional pain.

AF: Yes, that was step one for me, to teach my body a new story so that it would stop telling the one about how broken and wrong it was. And I did get there. I started to go through this healing, this transformation after that experience on the trampoline, in my late twenties. I started asking myself more questions. Is this pain still real? What does it say about me that I’m always in pain and am not suffering from a disease or an underlying condition? That I have no real reason to be so? I started to seek out healers who would help me answer these questions. I started to work with an osteopath and a physical therapist, and I did traditional psychotherapy for years, sometimes even a few times a week. I did a lot of work on myself to change my story and my relationship to my body, until I finally got to a place in my thirties where I could actually do an entire marathon and not feel broken after it. Once I did that work, and strengthened my body, and found a new relationship to it, then I could start to listen to it. To trust it when it was telling me something.

AT: I feel like your relationship to your intuition is really strong —

AF: Yes, it is, and I can feel it very presently in my body —

AT: And acutely —

AF: Yeah, literally right here between my ribs.

AT: You know that expression shoot from the hip? I feel like you shoot from the gut. That’s who you are. Do you ever second-guess that shot?

AF: Yes, of course I do. That’s the other part of intuition I mentioned — the part of yourself that is still learning, that maybe doesn’t have the answer yet, or is unsure if what you’re feeling is your intuition or past traumas manifesting somehow and taking over in the moment. I am very cognizant of that.

AT: This describes something that I think a lot of women face: a pendulum swing of second-guessing yourself, of wondering if what you are feeling is the motivation of your new story or your old story — of old traumas or new relationships to the self.

AF: Exactly. It isn’t until you are fully connected to your body that you can sense when that old story is trying to take over and you can instead push past it. This is how you flex your intuitive muscle.

AT: Tell me more about that muscle.

AF: I think that our intuition is like a muscle, and if you don’t use it, it atrophies. If you don’t use it or don’t even know how to identify it, then you also don’t even know that you have intuition or it exists to begin with.

AT: Like my abs.

AF: Like your abs. And the way that you get stronger in your intuition is by using it, working it out. By having the courage to act on your intuition, to listen, to actually pay attention to and be in constant consultation with it.

AT: I am thinking about that scene in the finale of season three of “Succession” when Gerri looks a groveling Roman dead in the eye after he begs her to save his legacy, and she softly says, “It doesn’t serve my interests. How does it serve my interests?” So cutthroat. So good.

AF: And we have to let our intuition ask those cutthroat questions! We have to let our intuition be selfish. Because if our intuition is speaking to us and we just choose to ignore, ignore, ignore, it goes away, or it gets silenced, it gets very dull. You have to let it ask the outside world how your interests are being served, even if that makes you incredibly uncomfortable or terrified or even disliked. And then you have to act on what that intuition is telling you. It could be easy, or it could be really hard, like telling your friend how that thing they said or did made you feel —

AT: I apologize for that, by the way.

AF: How does the way you cooked me those eggs serve my interests, Amber? It doesn’t serve my interests.

AT: What’s it like to have a number one best friend like me, and how do the other numbers feel about it? It must be very hard for them.

AF: It is so hard. And yes, intuition is a muscle that you must flex even when you don’t want to. I’ve gotten stronger and been able to pinpoint what I feel and how I feel it. I know in the moment, when I get that feeling in my gut, a holding or a flowing, either way I know what’s right for me, and yes, maybe it’s going to be uncomfortable to act on it, but I’m going to do it. And then once I’ve done it, everything feels so much better and so much more aligned, like a good workout.

AT: You’ve worked out that intuitive muscle!

AF: Yep! And after you do it one time — even just once — you now know about that muscle and how to get it to work for you. That it is there to serve you. You learn that listening to your intuition, even if it’s hard, will always end in a better outcome. It’s like, Oh, what’s that feeling? Oh, I’m getting a message from myself about something that’s not working for me. Am I going to ignore that message? Am I going to live with that message? Am I going to fester in that message? Or am I just going to listen to it? Act on it? And when you act on it, it may not always be 100 percent right, but at least you’re headed in that direction. You’re stretching and strengthening that muscle.

Excerpted from “Listening in the Dark: Women Reclaiming the Power of Intuition,” edited by Amber Tamblyn © 2022 by Amber Tamblyn. Used with permission from HarperCollins/Park Row Books.

Image Sources: Courtesy of Harper Collins and Getty Images / Corey Nickols